There are a lot ongoing discussions about what makes Hong Kong Hong Kong, perhaps since the handover in 1997. A symptom of decolonisation. Yet at the same time there are a lot of discussions about cultural preservation, about keeping aspects of ‘The Real Hong Kong’ for prosperity, in case things change. Colonisation was a process; so too is decolonisation. Preserving and studying the past is certainly important at this juncture, but indulging in or consuming nostalgia is something else. There are no such things as ‘The Real Hong Kong’ or ‘The Real Hongkonger’. In fact one should be cautious of this way of thinking. Change is inevitable, and whether for better or worse is a matter of perspective. Whether one likes it or not, Hong Kong as a concept is continuously evolving. Waxing nostalgic does not get us anywhere. If I had to name one quality that has been eroding in Hong Kong since 1997, it would be its open-mindedness: its capacity to embrace different ideas, whether global, regional or from the Mainland. That pragmatic, flexible and versatile mindset placed us uniquely on the global stage. A global outlook opens us up to infinite possibilities as well as opportunities. An island mentality is stifling. This means considering Hong Kong in context of the rest of China, Asia and the world. The fact that we were brought up in colonial Hong Kong without a sense of nationality should be used to our advantage. We were once not afraid to not define ourselves. We grew up in a third culture: not exactly Chinese, not exactly British, but somewhere in between. This is manifested in our language, food, temperament, outlook and way of life. Rather than rushing to define ourselves, we could leverage this ambiguity to look into the future. What I have just written does not preclude the political reality of Hong Kong at the moment, and what happened here in 2014 and 2019. However challenging it might be, we need to face forward and step into the future with optimism.

(Woke up in the middle of the night and wrote this in Byword. The events of 2014 and 2019 have made Hongkongers either very heated or deepy lethargic towards conversations of this kind. I’ve probably not considered these ideas too carefully or from every possible angle. I’ll simply park my thoughts here, and let them percolate and evolve.)

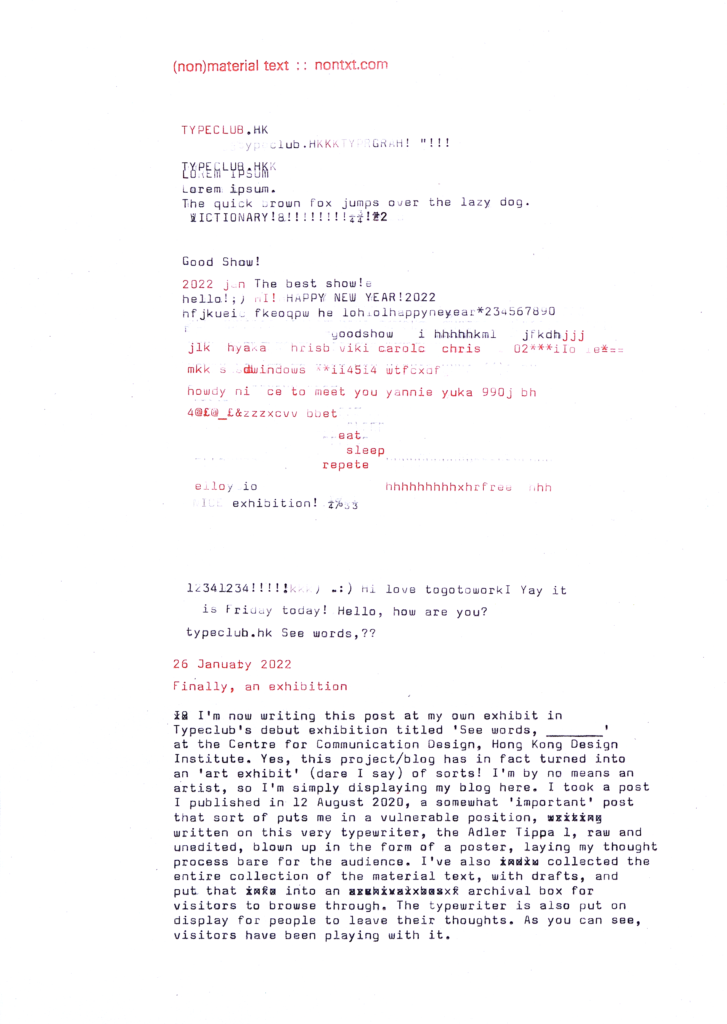

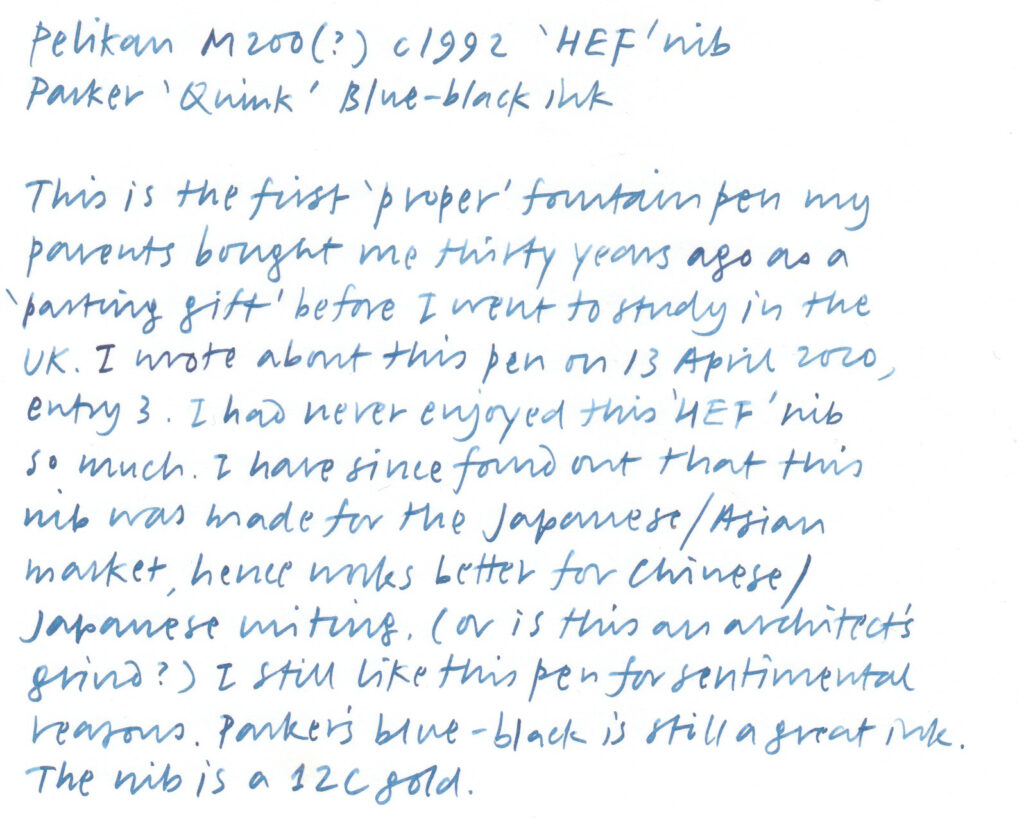

![A writing sample written with a fountain pen. The text reads:

Pelikan 400NN c1950s 'EF' nib

Montblanc Midnight Blue ink

A 'vintage' Pelikan possibly from the 1950s. A flexible 14C gold nib that's very pleasant to write with. A all pen with subtle green and black translusent [sic] striations on the barrel. A beautiful writer.](https://nontxt.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/pelikan-400nn-sample-1024x444.jpg)

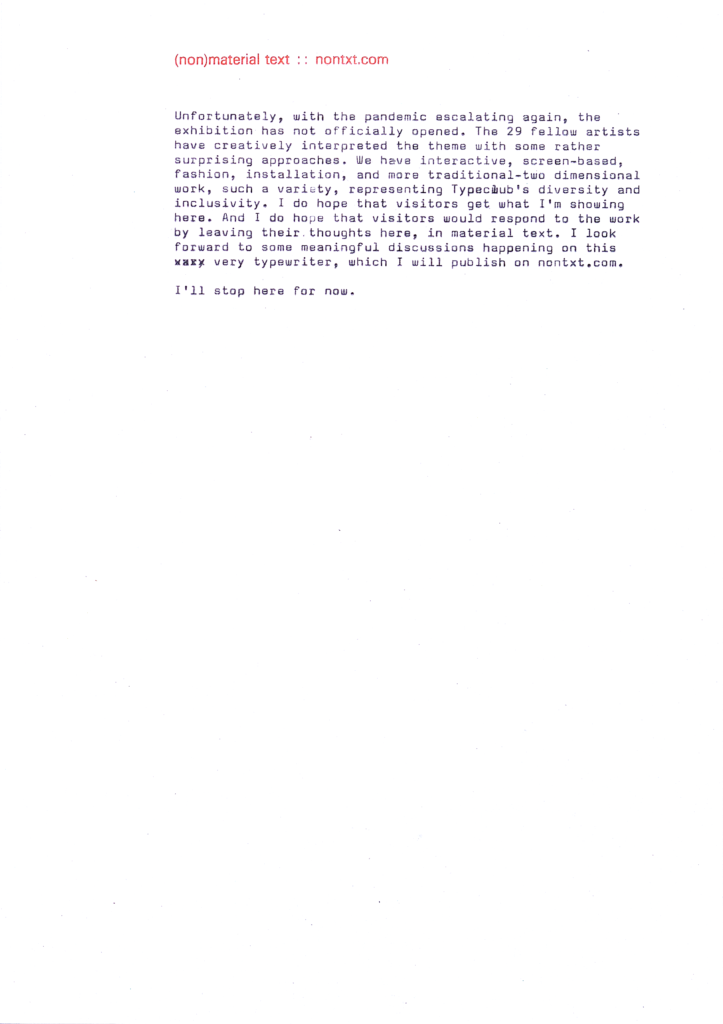

![A writing sample written with a fountain pen. The text reads:

Pelikan Souverän M605 Stresemann

'F' nib Diamine Oxford Blue ink

This is my most expensive Pelikan to date. A classic yet understated pen design, more subtle than the regular green or blue stripes with gold trim. The grey strips are an homage to Gustav Streseman [sic], a Nobel Leave Prize recipient in 1926. Streseman [sic] is attributed for a kind of suit with thin grey stripes, hence the name of this pen. Souverän is Pelikan's flagship series. The numbers refer to the size of the pens and nibs, from 100–1,000, 1,000 being the largest. I find the size of this 605 perfect for my hand. The nib is Rhodium-plated 14C gold, which writes extremely smoothly. Very enjoyable to write with. Though the 'F' nib is a tad too think for my handwriting. This is now my favourite pen in my entire collection.](https://nontxt.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/pelikan-m605-sample-1009x1024.jpg)

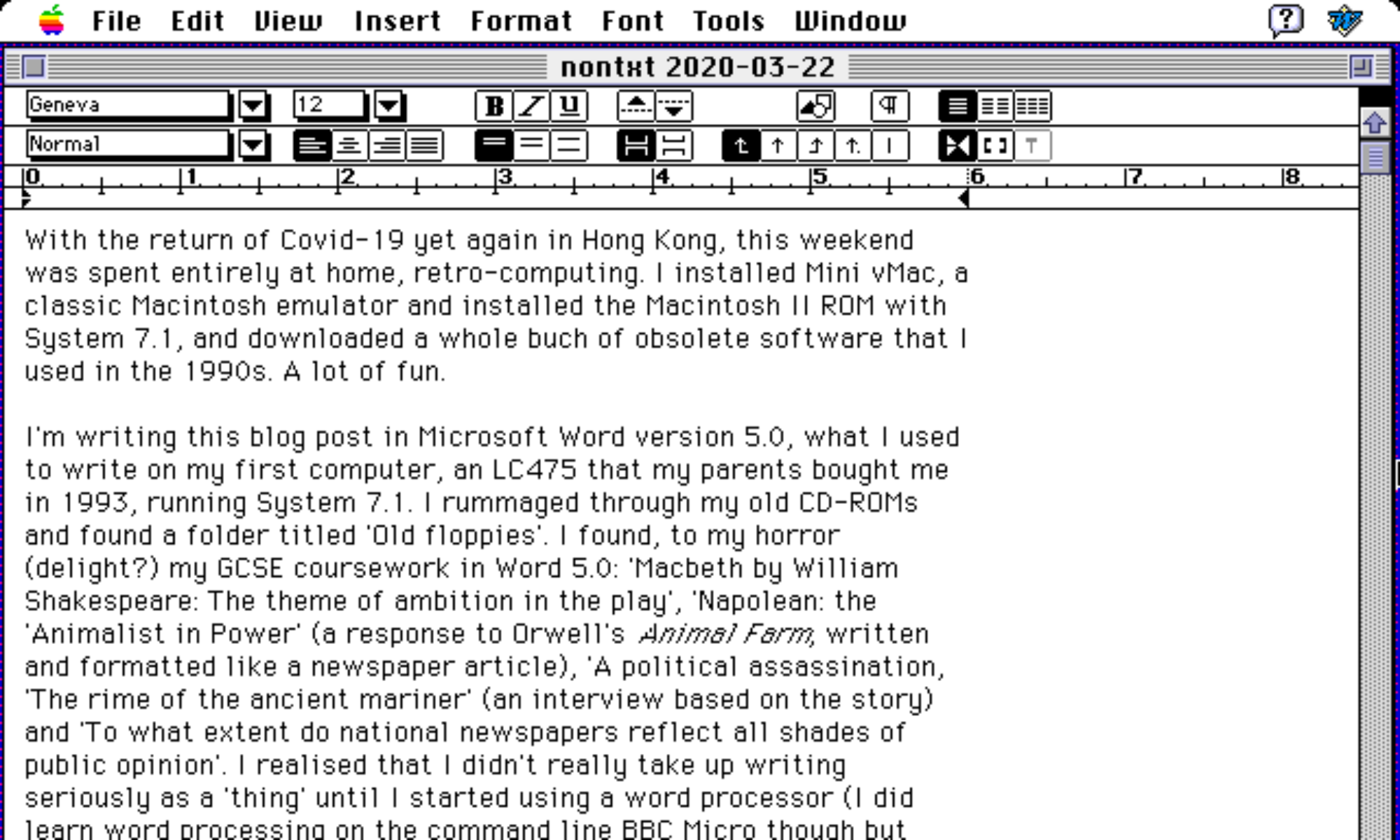

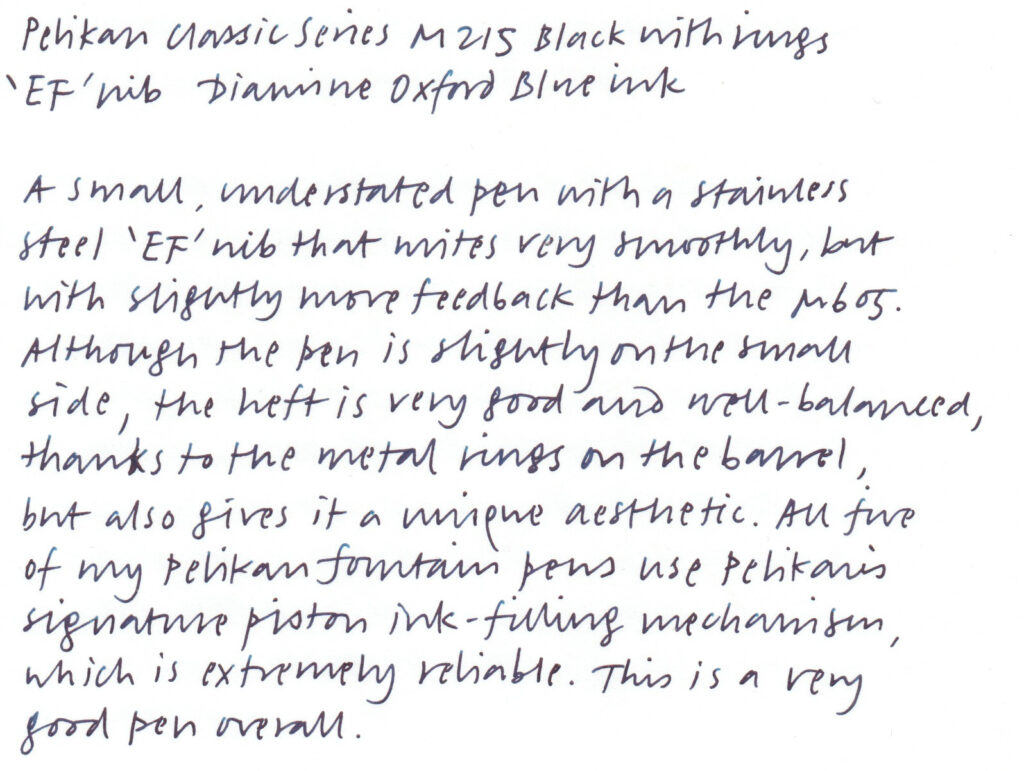

![A writing sample written with a fountain pen. The text reads:

A retro relaunch of Pelikan's classic 10 school pen from 1955. This is a 018 special edition that comes with a retro style presentation box with a bottle of ink (the ink I'm using now). The pen's styling is quite minimal in a beautiful blue and gold trim. The gold-plated stainless steel [nib] is surprisingly thin for an 'F' nib, and it's very flexible. A very leasing pen.](https://nontxt.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/pelikan-m120-sample-1024x604.jpg)