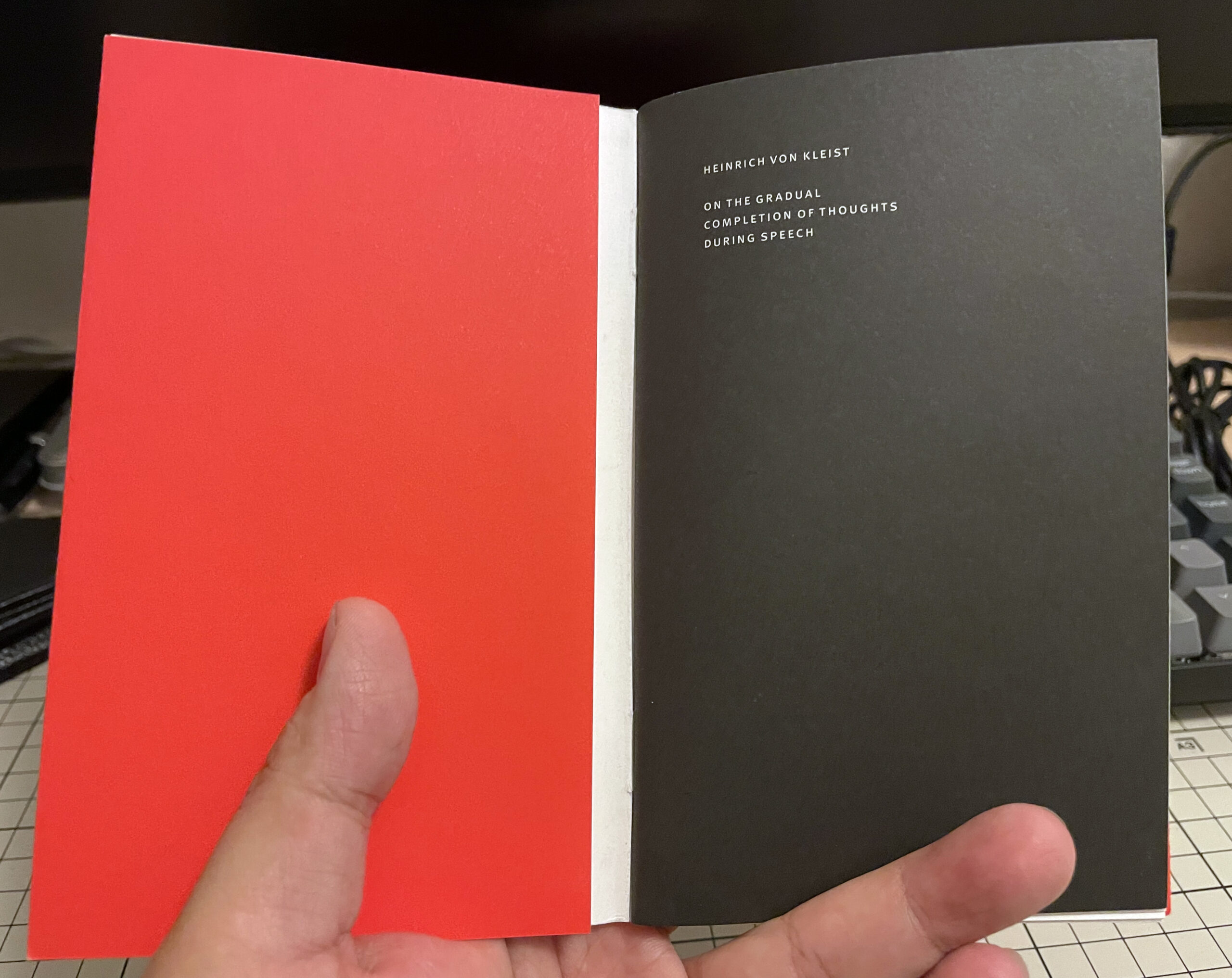

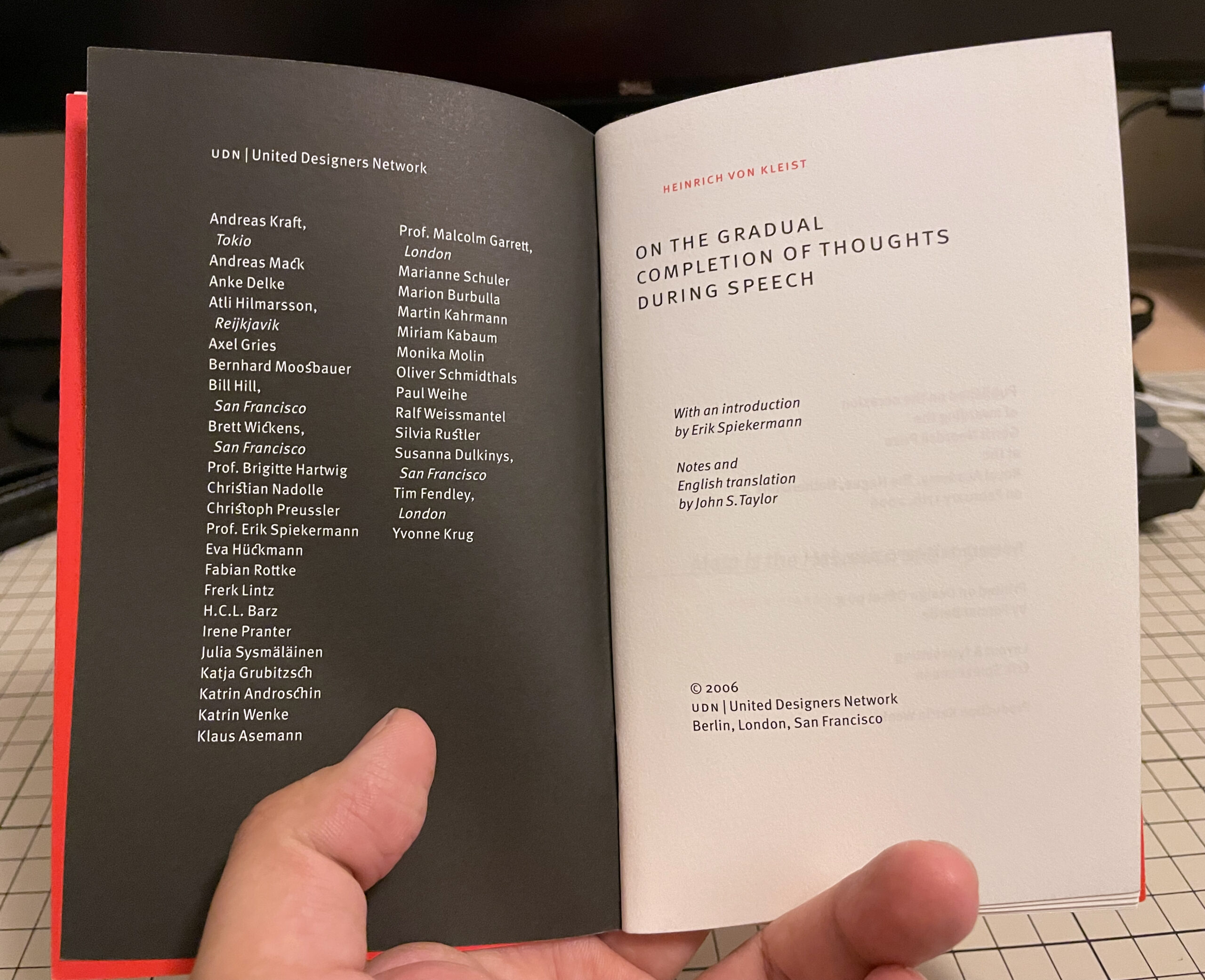

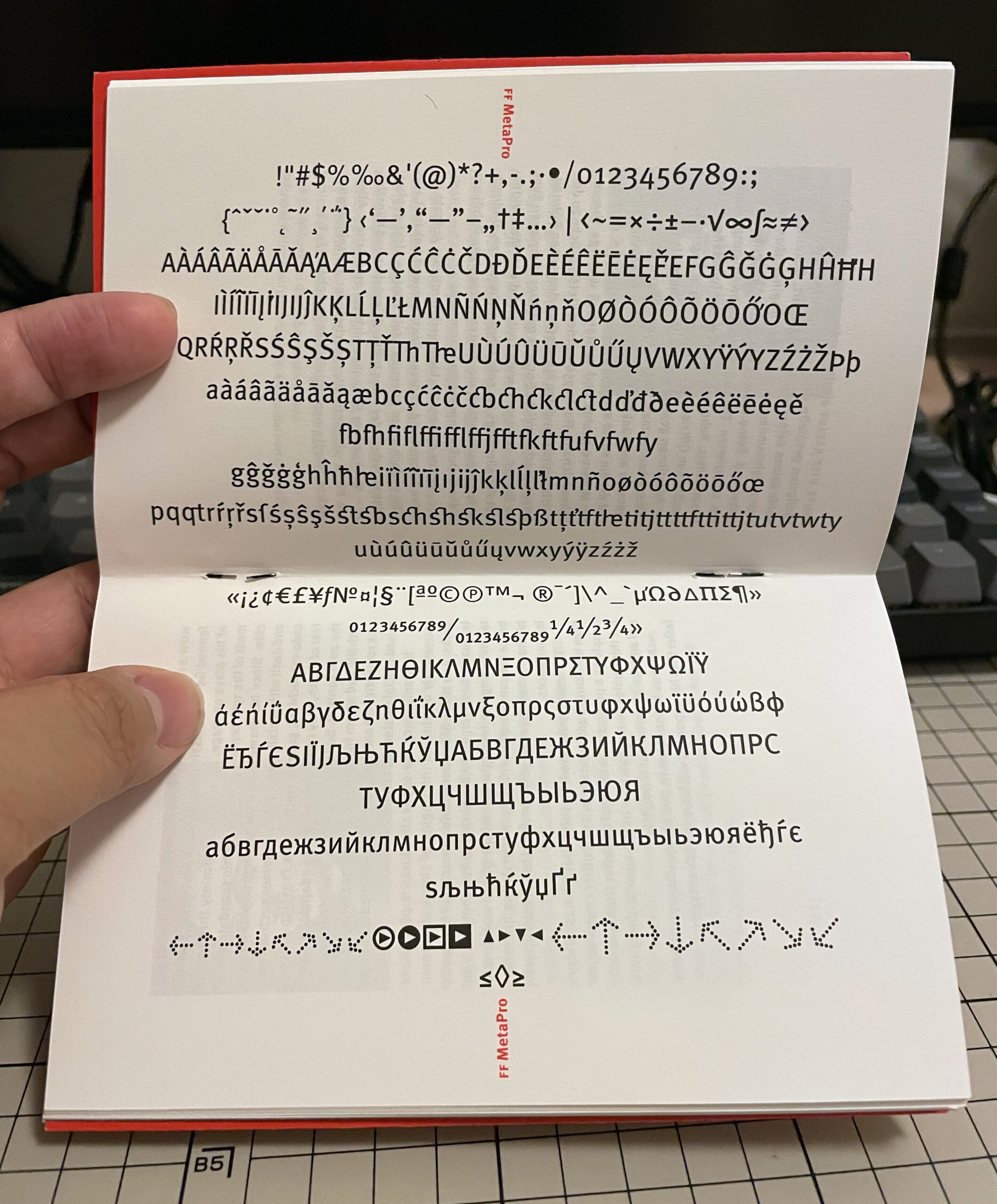

This charming little pamphlet was gifted to me by a dear colleague who has just retired. Designed and typeset beautifully by Erik Speikermann and set in his FF Meta Pro typeface (I suppose this is a type specimen of sorts), its content is an essay by Heinrich von Kleist titled ‘On the gradual completion of thoughts during speech’. Both the original text in German and an English translation by John S Taylor are contained within, with an introduction by Speikermann, a biography of Kleist and some translator’s notes.

[A different English translation of the essay by Michael Hamburg titled ‘On the gradual construction of thoughts during speech’ can be found here.]

This is of course a neat little designed object, but I was more intrigued by the essay. ‘Thinking out loud’ is a typical apology that we prefix any tentative thoughts we utter when conversing with others. In this short essay, Kleist argues that we do that all the time, and even great orators use speech as a gradual process for structuring thoughts:

I believe many a great orator, even in the moment he opened his mouth, did not know what he would say. He made a bold start, leaving what was to come to luck under the conviction that he could achieve the required clarity of thought and heightening of his mental faculties from the circumstances.

As a lecturer, I quite often find myself in the exact situation. I would happily ad-lib my way through any given occasion with nothing but a loose conception of what I am to speak about. This happens even at conference presentations, after the aptly named ‘abstract’ has been accepted and a slide deck cobbled together. Scripts have never been my friend; having to follow a script word for word is torture for both speaker and audience. No two presentations can therefore be the same. This can be extremely daunting. Control is given up to allow for more freedom and happenstance. It’s risky.

It follows that a slide deck cannot capture what actually happens in a presentation. A slide deck is only a visual aid, not a documentation. It’s an entirely different document genre. Ad-libing and then transcribing into text would also be a shift in genre, which is similar to ‘stream of consciousness’ writing, but rather different from the process of writing and editing.

Kleist’s essay made me realise the potential richness of conversations as a means to think things through. Building your own thoughts on others’. Allowing your mind to be shifted as new information and points of view emerge. Entering a conversation with no assumptions or preconceived notions. Realising that it is okay to waver and not have a fixed point of view. These might be prerequisites for meaningful and thought-provoking conversations as a means to structure tentative thoughts. Good conversations are hard to come by, and I believe that meaningful conversations are important in a world that is becoming more polarised and ideas become more extreme.

Kleist writes that the processes of ‘conception’ and ‘expression’ need to work hand-in-hand, and unclear expression doesn’t necessarily mean unclear conception. He suggests that a command of speech would be indispensable. He continues: ‘he who speaks faster than his opponent will have the advantage, since he has more troops in the field.’ I can see a parallel in writing drafts, or even sketching as a conceptualisation method.

This seems akin to using writing as a process to structure thoughts, as I wrote on 25 July 2020:

Making thoughts visible or material allows one to organise ideas in a tentative way, not having to commit to anything until completely satisfied. Making thoughts visible is important, as it allows one to toy with ideas, reason through, assess options, iterate, clarify, etc.

On another note, New York Post published an article on some research done in Japan which found that the act of writing with pen and paper aids memory and recall more effectively than taking notes on digital devices (mobile phone and tablet), even when using a stylus. I’ll park the link here and come back to more discussions on this topic later.

(written in Byword on the MacBook Air, revised in WordPress on an iPhone 12 Mini)