Sulki and Min’s cerebral, intelligent work really strike a chord with me. I was fortunate enough to be at the opening of their latest exhibition Sulki & Min: Obscuring & Clarifying in Hangzhou earlier this week. Their experience studying and working in the Netherlands, studying under Sheila de Brettville at Yale, their influences from Robin Kinross’s writings as well as Jan Tschichold’s typographic ethos made for a theoretically-grounded and almost academic praxis to graphic design and typography. I am deeply mesmerised by their oeuvre.

For the Hangzhou exhibition, they translated a small booklet titled Explained into Chinese, which was first published in 2017. The booklet contained rationales for each project on display at the exhibition, unillustrated. Readers could read the rationales at the exhibition while viewing each work by referring to the numbers, or read it away from the work and imagine what the work might look like, much like reading a work of fiction. The text paper is a glossy coated stock, with the cover and endpapers in a rather commonplace leather-like textured paper that one might find in a bog-standard printshop. The text is set in a single size and weight of (I believe) Lanting Hei and Univers. The cover is a curious, abstract graphic foil-blocked in white on the red paper. I read it as three lines of illegible text, blurred. The design is visually austere yet conceptually captivating.

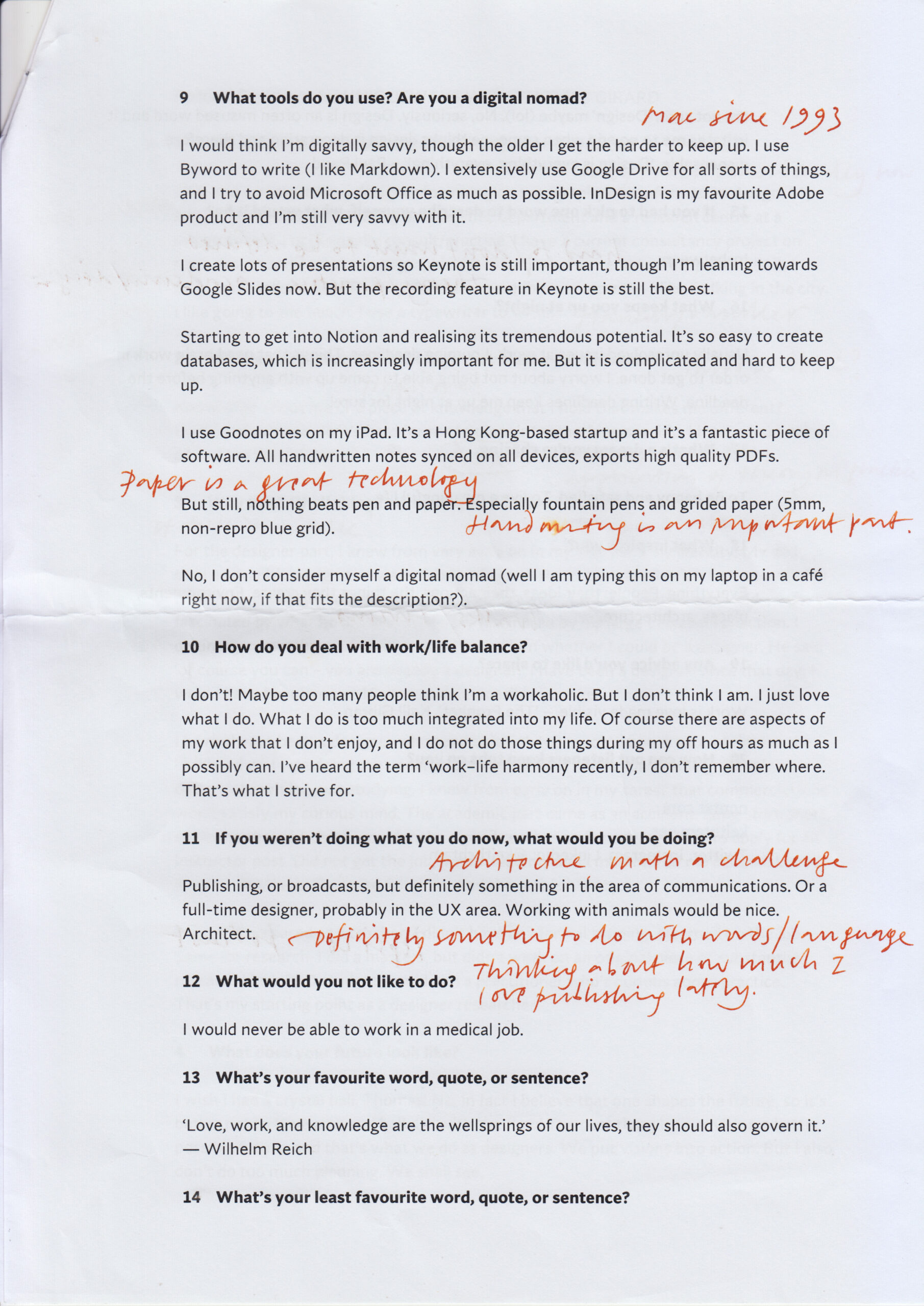

Another publication titled Explain Explained is a saddle-stitched booklet contained in a simple grey chipboard slipcase. The self-cover booklet is printed on a light-weight, lightly coated stock. The fore-edge is left untrimmed, hence creating a v-shape slanting in two directions. This coincides with how the bilingual texts are organised: Chinese opens on one side, and English the other, flipped head to tail. This subtly enables the reader to place their thumb on the fore-edge and easily flip the pages for a specific language and stop right in the middle where the two languages meet. The extent of the text is short, yet the content is rich with nuggets of insights into the duo’s background and design philosophy. A conversation with Sulki and Min are organised into five sections, followed by two short essays by Lu Tao and Gideon Kong. Again the text is set in a single size and weight, this time in Grotesque Classic (for English) and Monotype Hei (for Simplified Chinese). I enjoyed the layout of the dialogue where a thin rule is drawn vertically through the centre of the page, with Sulki’s answers occupying the left column and Min’s answers on the right. Where one answer ends, the other answer begins on the same line; the questions are indented and run across the dividing rule. This schema is simple yet extremely well considered, and subtly suggests the duo’s complementary working relationship. It makes for a delightful reading experience. I capture two quotes that particularly resonated with me here:

‘[…] I don’t think [cultural identity] is something you should seek. On the contrary, it should be something that comes despite yourself. Something that you can’t help, or something that it’s just fine to leave traces of in your work.’ — Choi Sulki

Sulki: ‘I feel the whole business of wanting to be someone, including your “true” self, is just a waste of time. You are what you are, no matter what you or other people think. You need to acknowledge it and nurture it, but you shouldn’t feel that you are deprived of yourself. It just doesn’t make sense.’ — Choi Sung Min

The souvenir folder, with a deadpan paragraph of descriptive text screen-printed in white on a pedestrian stationery store folder in turquoise, is also a conceptually interesting piece that I quite enjoy.

Sulki & Min: Clarifying & Obscuring

24 March–26 May 2024

Noon–6pm daily, closed on Mondays

Transtage

211, B Block, JNA Art Park

415 Chengye Road, Binhiang District

Hangzhou

(Written on the Freewrite Alpha and edited in the Mention app and WordPress)