I’ve been thinking and reading a bit about writing recently. From my experience, writing can be both a satisfying and an excruciating process. We’ve all suffered from ‘writer’s block’: deadline looming, nothing is coming out. Not a minute passes without worrying sick about that f*cking piece of work that needs to be done. More time is spent worrying about writing than actually writing, wanting everything to be perfect in one shot. Paul J Silvia, in his excellent book How to write a lot: a practical guide to productive academic writing suggests that a writer’s block is ‘nothing more than the behavior of not writing’. An interesting thought.

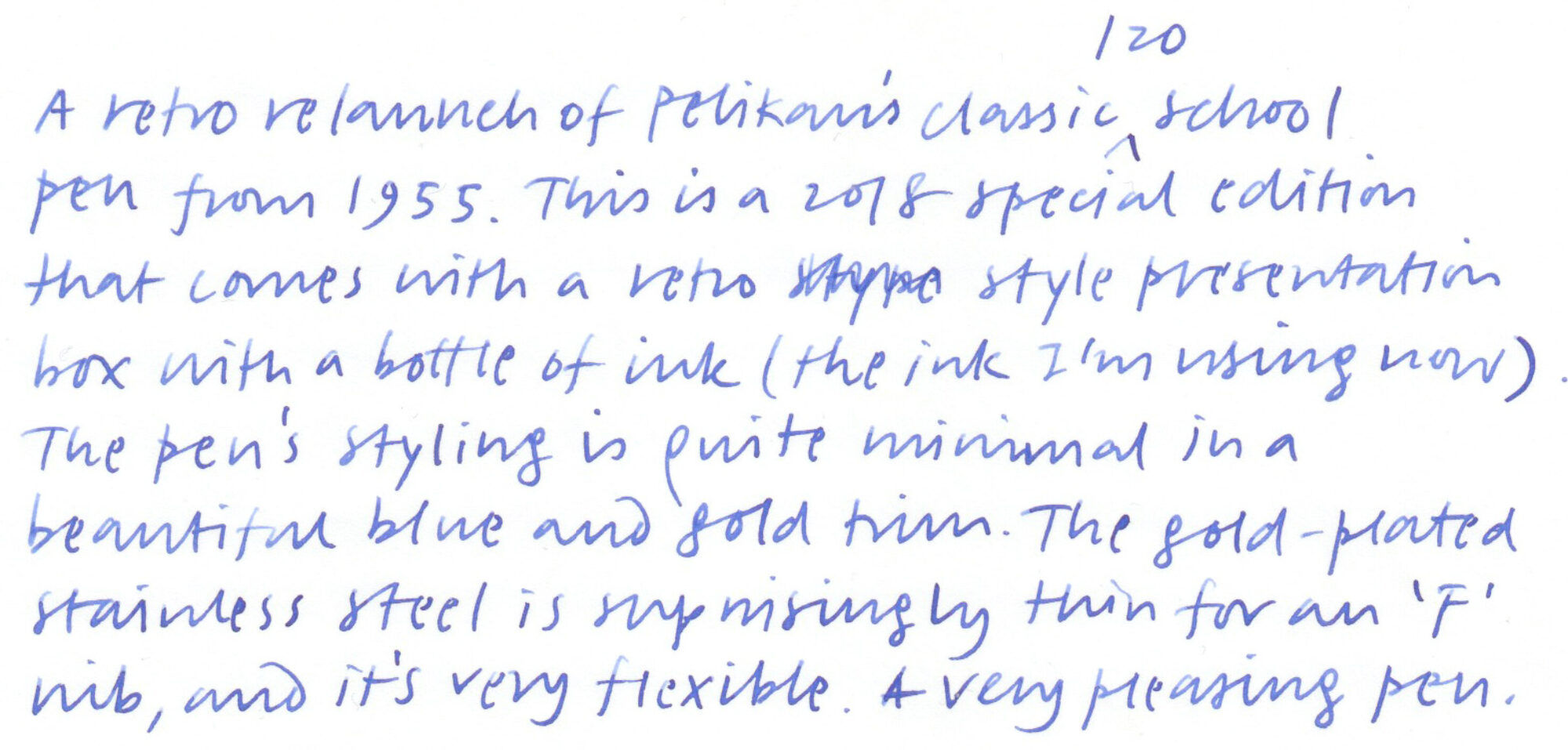

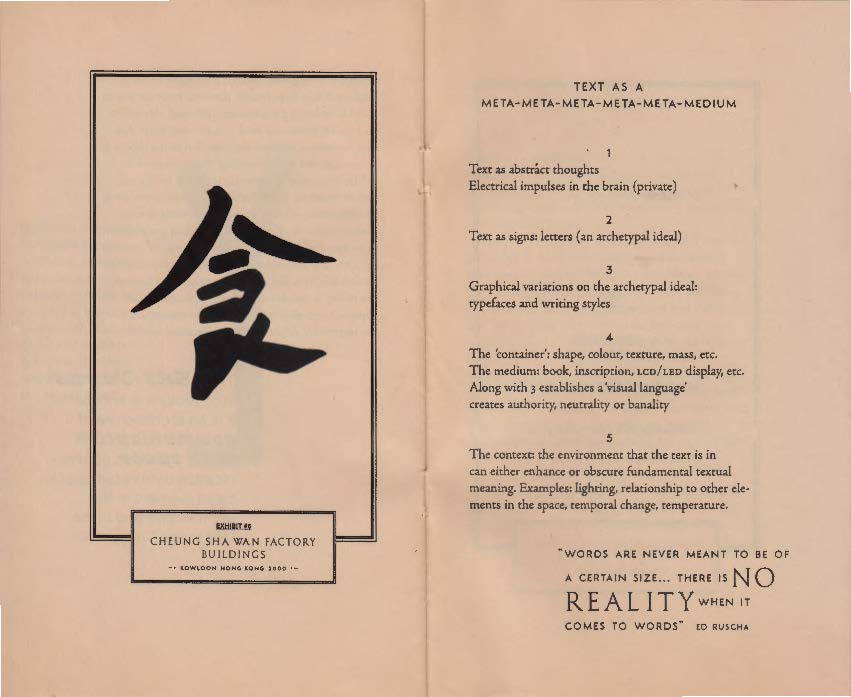

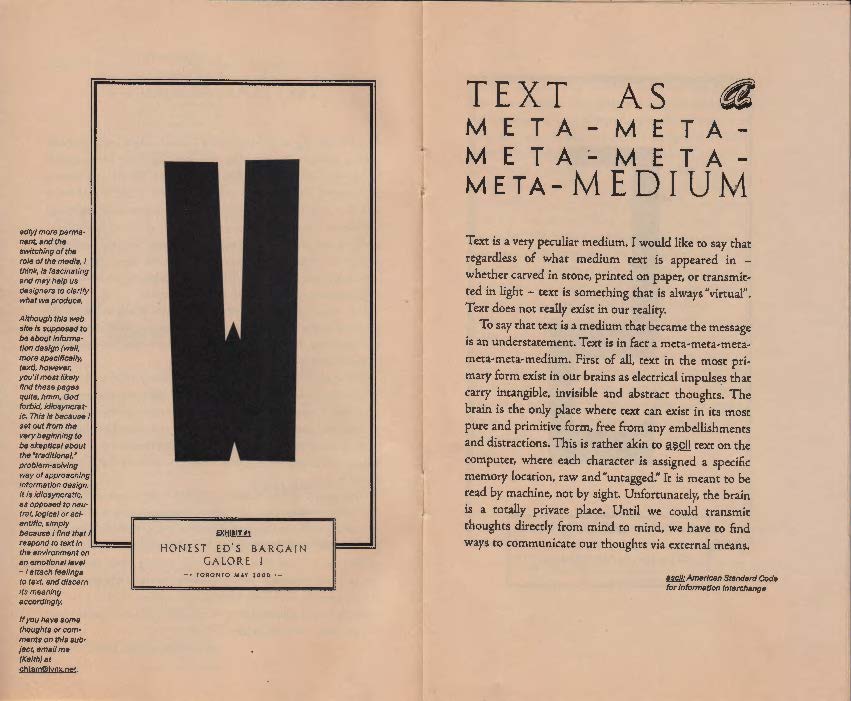

I’ve often fallen victim to this way of thinking myself, even though I actually enjoy writing and think that my writing is not half bad at all. After thinking a little bit more, I came to this realisation: the act of writing is the visualisation of abstract ideas. Without externalising these snippets of thoughts from our brain to a medium where we can see everything in front of us (on a screen, a piece of paper, etc.), it is difficult to make sense of it. Mulling over ideas in your head instead of putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) is precious writing time wasted because we’re not visualising.

Jeff Goins in his Medium post suggests that what we call ‘writing’ is not a single process but a three-part one: ideation, creation, and editing. I tend to agree, but I don’t see them as clear cut at all. I see writing itself as an ideation process where you ponder on possibilities and try out different things as you write. Editing can also kick in during this process, where you continually refine and restructure ideas, and remove irrelevant ones. Of course, when you turn a manuscript to an editor, the editing process proper kicks in.

Another thing to think about is structure, which is also about visualisation. With current writing tech this is easy to do: organise things into paragraphs, headings, even folders, tags, colours (Scrivener is an excellent app by the way for structuring writing, and for playing with structure). In a regular word processing app like Microsoft Word, (semantic) structure and visual presentation are the same: typographic attributes are used to code different things like levels of headings, etc. But apps that use Markdown let you use simple codes to semantically structure your writing without worrying about typography, and the structure is preserved when you export the text. I tend to not write in ‘focus mode’ – it is important for me to see the structure when I write (although this blog intentionally does not have any headings at all – something I will discuss later).

(I started writing this post in the Flowstate app under a five minute time limit. I was forced to get words out with no opportunities to edit at all because the app would delete everything after three seconds of inactivity. I continued writing in Byword and now only one sentence from that writing session remains. Not the kind of pressure I need and does nothing to my creative process. Writing freely has its benefits, but not when under pressure – at least for me.)